As I continue to review the Valuation Office House Books for the town of Dunmanway, my knowledge of the ‘past lives’ of a variety of structures ranging from the domestic to the business, educational, and religious is extended and enriched by looking back through these records.

Indeed, the faintest inscription found within these manuscripts can potentially open a door into the past giving a clearer understanding of the wider community my forebears lived in and events they were witness to.

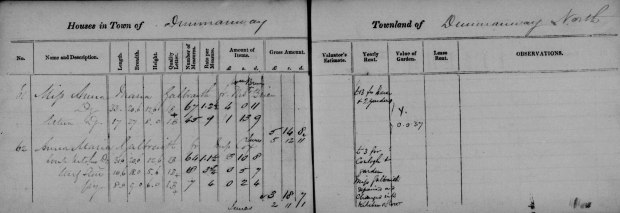

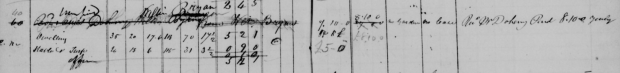

Soup kitchen entry as recorded in the Dunmanway 1848 and 1851 House Books

An example of this distant echo is found in the 1848 House Book entry for no. 62 Main street under the ‘Name and Description’ column:

‘Anna Maria Galbraith from Miss Cox

– Soup kitchen Dg

– Turf store

– Privy’ 1

Continuing across to the ‘Yearly Rent’ column:

‘£3 for cowlogh [sic] & garden Miss Galbraith repaired and changed into a kitchen and store’ 2

While the written word ‘soup’ is not the clearest, cross-referencing the entry for the premises in the revised 1851 House Book confirmed the word. The surveyor’s scribbled note records:

‘At present to Miss Cox for soup house [sic]’ 3

And under the Observations:

‘No. 61 & 62 are one house but a separate take and no. 62 is at present let to Miss Cox for a soup kitchen but only per term [sic]’ 4

Figure 1. The 1848 House Book: no. 62 was graded 1B which reflects the construction material used and its then current condition: ‘1’ being a ‘slated dwelling house built with stone or brick and lime mortar’, and ‘B’, ‘medium, slightly decayed, but in good repair’. 5 As well as no. 62, Miss Anna Maria Galbraith is additionally renting the neighboring premises of no. 61 Main street. [Click the image to enlarge.]

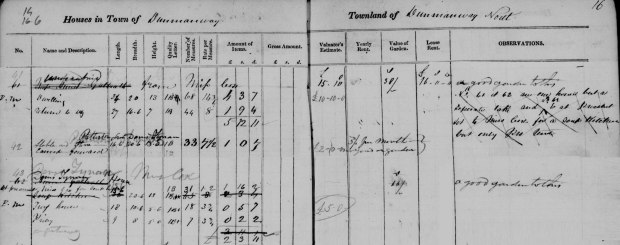

Figure 2. The revised 1851 House Book: as part of the 1851 revised house calculations, the house numbering sequence has changed across the town. No.62 is struck out and replaced with no. 43. While the different valuators handwriting in both ink and later in pencil is challenging in itself to decipher, the crossed out information, such as individual names, on site observations, as well as the words ‘soup kitchen’ makes the sequence of events post-1848 survey frustrating to interpret and clarify. However, the unmarked text of ‘at present to Miss Cox for soup house [sic]’ 6 suggests that the kitchen might have still been in operation in 1851 within the downsized unit of no. 43. [Click the image to enlarge.]

Figure 3. During the interim years between 1848 and the revised calculations of 1851, no. 62 was divided into two smaller lots – nos. 42 and 43.

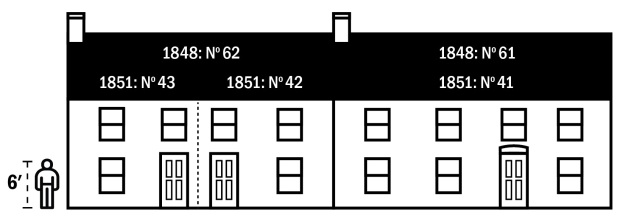

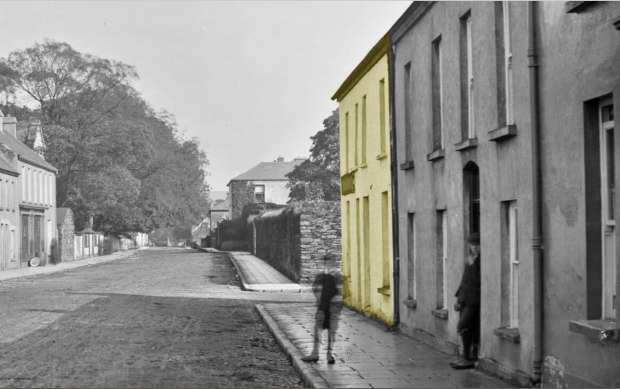

Figure 4. A present day view of the buildings on Main street. In the 1848 House Book, the whole of this yellow building was leased to Anna Maria Galbraith as one unit with a use of soup kitchen dwelling. According to the 1851 record, the building was divided into two: the left side, no. 43 appears to be still used as a soup kitchen by Miss Cox, but leased to a Denis Tynan. (The entrance has since been replaced with the central ground floor window, as seen in the image.) No. 42, on the right, was recorded as being a stable and store leased to Denis Tynan.

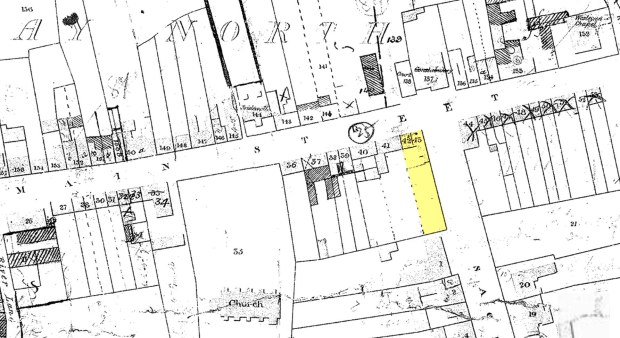

Figure 5. Nos 42 and 43 Main street (highlighted in yellow). This second edition Ordnance Survey (OS) map has the same house number sequence as the 1851 House Book. Did the Valuation Office follow the OS maps lead when updating their referencing system? [Click the image to enlarge.]

The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committee

Once I started to search the name Anna Maria Galbraith in relation to Dunmanway, I quickly uncovered some interesting connections to this building.

Both the lessee, Miss Galbraith and property lessor, Miss Cox were members of The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committee. As the name suggests, the Committee appears to have been formed to provide comestible aid to the local population effected by the potato crop failure caused by the ‘potato late blight’. Otherwise named Phytophthora (plant-destroyer) infestans7, this mold led the potato yield to diminish significantly three seasons out of four between 1845 and 18498 and resulted in a humanitarian crisis that culminated in the death of one million people through starvation, typhus and other famine-related diseases.9

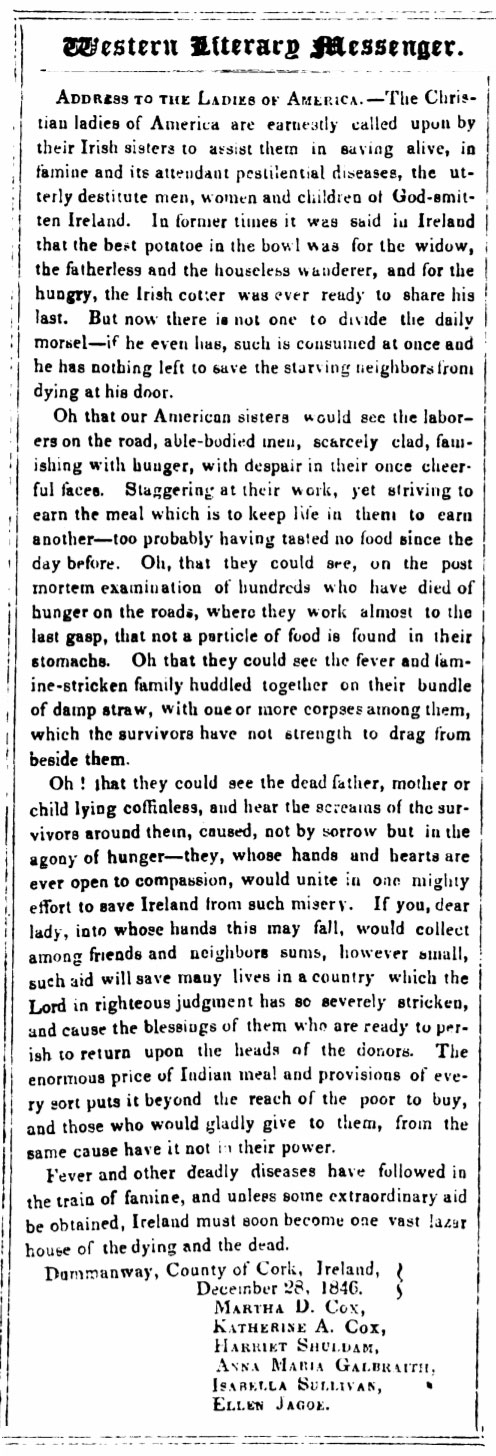

While the exact year of the Committee’s formation is not known to me at present, the earliest evidence I have been able to source regarding these gentlewomen’s shared philanthropic effort is in their moving appeal for aid to the ‘Christian Ladies of America’. Dated December 28th, 1846, the plea was published in The Western Literary Messenger, Buffalo, New York, February, 1847.10 This would suggest that the Committee was established in late 1846 as a result of the return of the blight for the second year in a row after the initial outbreak of 1845.

Figure 6. This private charity’s address contains heart-wrenching imagery of people unable to source affordable food, ‘famishing with hunger’, working on public relief programmes for little pay, ‘hundreds…have died of hunger on the roads’. The ‘enormous’ price of the Indian meal is highlighted making it a commodity outside the means of the poor and destitute, who had depended on the potato as a source of subsistence. ‘Fever, and other deadly diseases have followed in the train of famine, and unless some extraordinary aid is obtained, Ireland must soon become one vast lazar house of the dying and the dead.’ 11 It was this bid to the Ladies of the United States that lead Vice-President George Dallas read their message at a meeting for Ireland held in Washington on 9th February, 1847.12

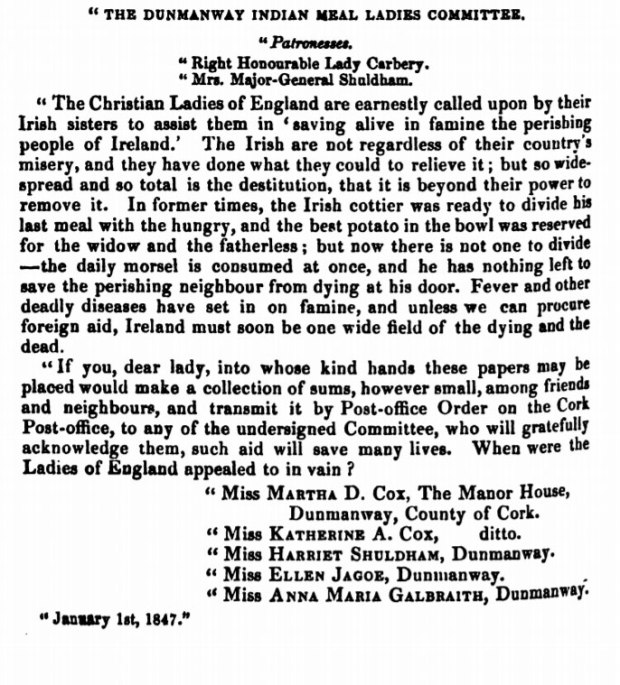

In yet another public appeal, this time from The British Magazine dated a few days later in January 1847, the Committee calls upon the ‘Christian Ladies of England’ to assist their Irish sisters in ‘saving alive in famine the perishing people of Ireland’.13

Figure 7. The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committees’ 1847 appeal seeking funding so to be able to purchase Indian meal. The potato had become the staple part of the Irish diet, with cereal-based foods unavailable to most of the poor due to increasing prices. The importation of Indian meal as a cheaper form of relief food first occurred in the early 1800’s to compensate when potatoes were scarce. Somewhat exotically named, Indian meal originated in America and is milled whole maize grain. In some cases difficulties in grinding the corn produced poorly refined meal which in turn caused digestive problems to those who had no choice but to eat it.14

The Committee members

Both appeals for funding contain a total of six names of women who all resided in and around the town of Dunmanway.

This small group making up The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committee was composed of sisters Martha Deane and Katherine Anne Cox of the Manor House, Miss Harriet Shuldham of Coolkelure, Miss Ellen Jagoe, Isabella Sullivan and finally Miss Anna Maria Galbraith. The Commitee patrons were Lady Carbury, and Mrs Major General Shuldham.15,16

The appendix at the end of the article lists what I have sourced on each Committee member to date.

The Committes’ soup kitchen

Further research indicates that with the aid of small grants from the government and the Irish Relief Association the women opened a soup kitchen. The evidence in the House Books suggest this dwelling on Main street could have been the location of the organisation’s charitable enterprise. As previously noted, the 1848 manuscript records that Miss Galbraith had taken a lease from Miss Cox and based on the notes made by the Valuation Office official, ‘has repaired and changed into a kitchen and store’.17

Figure 8. A contemporary image from The Illustrated London News dated January 16th 1847, showing the Society of Friends’ soup house in the city of Cork. [Click the image to enlarge.]

Figure 9. Entrance to Dunmanway, from the Bridge on the Cork Road: this engraving from a drawing by John Mahoney published in the Illustrated London News on the 20th February 1847 captures the town when The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committee was in operation. With sweeping clouds, sparse bare trees, a flooded and muddy road, the damp and stark view gives the viewer a sense of the bleakness experienced by the local population at this particular time of the year. [Click the image to enlarge.]

However, the government’s public assistance policy changed as the administration recognised the inefficiency of public work scheme as a solution. In February 1847 the Temporary Relief Act (Soup Kitchen Act) was passed which established a network of soup kitchens to feed the starving more cheaply and assist the overstretched Poor Law system.22 However, from autumn 1847, responsibility for famine relief was shifted almost entirely on the local poor law union, which was in turn supplemented by independent charities.23 Introduced less than a decade earlier through the Irish Poor Law Act of 1838, this state system of poor relief was accessible through either indoor (workhouse) or outdoor relief. It was these local Unions, by their nature of existence, would bear the brunt of the dark days of famine, fever and disease.

A network of CHARITIES

It should be noted that this Dunmanway all-female charity did not work in isolation. They operated alongside a network of women’s relief committees throughout west Cork and beyond. These included the Ballydehob Ladies’ Association (formed January 1847), the Schull Ladies’ Association as well as the larger Cork Ladies’ Relief Society, and the Belfast Ladies’ Association.24 It would be of interest to know if any communication between these groups existed and therefore shed more light on their efforts.

Figure 10. A detail from the Lawrence Photograph Collection of Dunmanway, circa 1911 of the premise on Main street highlighted in yellow. [Click on the image above for the full view of this location.]

Indeed, it would be worth finding additional information on this small enterprising female-lead charity. What did the local people across the social, economic and political divide think of the Committee and their efforts? And did The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committees’ kitchen have the desired impact in saving lives within the community during these dark days of the Great Famine?

appendix: The Committee members

Mss. Martha Deane and Katherine Anne Cox

Daughters of Henry Hamilton Cox, the two Cox sisters along with their brother Sackville Hamilton where the last generation of the Cox family to hold the family estate. This comprised of almost 7,000 acres, including The Manor House, and the town of Dunmanway.25

Martha Deane died unmarried aged 70 in July 1860, with her spinster sister Katherine Anne passing away some 29 years later in 1889.

Neither of the Cox sisters first name is given as charge for the property on Main street, other than Miss Cox. Therefore, it would be of interest to know which of the sisters held responsibility for the lease as per the 1848 House Book record and later overseeing the running of the kitchen based on the 1851 House valuation notes.

Along with their shared efforts in bringing comfort to the hungry in the soup kitchen, the Cox sisters also significantly reduced rents payable on their Dunmanway estate in an attempt to ease the effects of the famine in 1845.26 This act was later acknowledged with presentation of a silver tea service by the Revd James Doheny on the behalf of their grateful tenants.27

Figure 11. It is of additional interest that the Rev. James Doheny (1786–1866) leased the dwelling, stable and turf office adjacent to Miss Anna Galbraith on Main street. The building is the current location of the Dunmanway Garda Siochana Station. [Click the image to enlarge.]

Miss Harriet Shuldham

Miss Harriett Maria Catherine Shuldham (1823–1884) was the only daughter of Major General Edmund William Shuldham, Esq.(1778–1852) of Coolkelure, and Harriet Eliza Bonar Rundell of Somerset (1786–1848).

In 1852, aged 29, Miss Shuldham married the Rt. Hon. George Patrick Percy Evans-Freke, 7th Lord Carbery (1810–1889), son of Lady Carbery, who is patron of The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committee. Their daughter, Georgiana Evans-Freke (1853–1942), married Sir James Francis Bernard, 4th Earl of Bandon (1850–1924).

Harriett Maria Catherine Baroness Carbery died aged 60 at Phale Court, Ballineen, Co. Cork in 1884.

Miss Ellen Jagoe

Miss Jagoe may be the daughter of Abraham Jagoe of Kilronan and Kinrath.

Isabella Sullivan

Miss Sullivan may be connected to the Sullivan family of Bridgemount House.

Miss Anna Maria Galbraith

Other than the House Book records, and the 1846 and 1847 appeals, I have currently sourced two other records that link Galbraith to the town of Dunmanway. The first is the 1826 Tithe Applotment Books for the parish of Fanlobbus listing a Miss Galbraith holding land within the town. The second, a death notice dated 16th February 1835, for a Capt. Morgan Galbraith h.p. 27th (Inniskilling) Regiment of Foot.

REFERENCES

TEXT

- National Archives of Ireland (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

- National Archives of Ireland (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

- National Archives of Ireland (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

- National Archives of Ireland (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

- Magee, F. (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

- National Archives of Ireland (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

- Abbot, P. (n.d.). The Famine 1: Potato Blight. Retrieved from wesleyjohnston.com

- Crawford, M. (1995). Food and Famine. The Great Irish Famine. (C. Póirtéir, Ed.) Dublin: Mercier Press.

- Mokyr, J. (Jan 3 2019). Great Famine. Retrieved from britannica.com

- Address to the Ladies of America. The Western Literary Messenger (11 February 1847). (Vol. 7-8). Buffalo, New York: Thomas & Lathrops.

- Address to the Ladies of America. The Western Literary Messenger (11 February 1847). (Vol. 7-8). Buffalo, New York: Thomas & Lathrops.

- Kinealy, C. (2013). How good people are! The involvement of women. Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: The Kindness of Strangers.A&C Black Publishers.

- The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committees. The British Magazine (1847). (Vol. 31, p. 240). London: Clerc Smith.

- Crawford, M. (1995). Food and Famine. The Great Irish Famine. (C. Póirtéir, Ed.) Dublin: Mercier Press.

- Address to the Ladies of America. The Western Literary Messenger (11 February 1847). (Vol. 7-8). Buffalo, New York: Thomas & Lathrops.

- The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committees. The British Magazine (1847). (Vol. 31, p. 240). London: Clerc Smith.

- National Archives of Ireland (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

- Kinealy, C. (2013). How good people are! The involvement of women. Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: The Kindness of Strangers.A&C Black Publishers.

- Kinealy, C. (2013). How good people are! The involvement of women. Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: The Kindness of Strangers.A&C Black Publishers.

- Daly, M. (1995). The Operations of Famine Relief. The Great Irish Famine. (C. Póirtéir, Ed.) Dublin: Mercier Press.

- Kinealy, C. (2013). How good people are! The involvement of women. Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: The Kindness of Strangers.A&C Black Publishers.

- Crawford, M. (1995). Food and Famine. The Great Irish Famine. (C. Póirtéir, Ed.) Dublin: Mercier Press.

- Kinealy, C. (1995). The Role of the Poor Law during the Famine. The Great Irish Famine. (C. Póirtéir, Ed.) Dublin: Mercier Press.

- Kinealy, C. (2013). How good people are! The involvement of women. Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: The Kindness of Strangers.A&C Black Publishers.

- Kinealy, C. (2013). How good people are! The involvement of women. Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: The Kindness of Strangers.A&C Black Publishers.

- Culbert, M. (2011). Cox Silver Tea Service. Dunmanway Historical Association. Retrieved from dunmanwayhistoricalassociation.com

- Dohenny, J. (1846 March 20). Address: From the Tenantry of the Misses Cox, Manor House, Dunmanway, to those Benevolent and Estimable Ladies. Cork Examiner. Retrieved from findmypast.com

IMAGES

- National Archives of Ireland (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

- National Archives of Ireland (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

- McCarthy, F. (2018). Front view of the dwelling house of no. 61 and 62 Main street as per 1848 housebook. Writers own image.

- Google Maps. (2018). Main Street, Dunmanway. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/ycoo8dlr

- Findmypast (2019). Griffith’s Survey Maps & Plans, 1847-1864. Retrieved from findmypast.ie

- Address to the Ladies of America. The Western Literary Messenger (11 February 1847). (Vol. 7-8). Buffalo, New York: Thomas & Lathrops.

- The Dunmanway Indian Meal Ladies’ Committees. The British Magazine (1847). (Vol. 31, p. 240). London: Clerc Smith.

- The Illustrated London News.(Jan.16 1847), The Cork Society of Friends’ Soup Kitchen. London: The Illustrated London News & Sketch Ltd. Retrieved from findmypast.ie

- The Illustrated London News.(Feb. 20 1847), Entrance to Dunmanway, from the Bridge on the Cork Road. London: The Illustrated London News & Sketch Ltd. Retrieved from findmypast.ie

- French, R., & Lawrence, W. (ca. 1865-1914). Carbery Place, Dunmanway, Co. Cork. The Lawrence Photograph Collection, National Library of Ireland. Retrieved from: nli.ie/Record/vtls000317663

- National Archives of Ireland (n.d.). Valuation Office House Books. Retrieved from census.nationalarchives.ie

Additional RESOURCES

Dunmanway Board of Guardians (Ref. IE CCCA/BG/83), Cork City and County Archives

Reflections on the Dunmanway Union, and its Workhouse, During the Great Famine

When Famine Devastated West Cork

Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 02 January 1847

Illustrated London News, 20 February 1847

Mallow Field Club Journal: Mallow Archaeological & Historical Society

Irish American sisters return Famine heirloom silver to Cork

The American Phytopathological Society

Very interesting I would love a copy of all

LikeLike

Hi Kathy, Glad you found the research of interest. The House Books of the Valuation Office are available to search on the National Archives of Ireland website: http://census.nationalarchives.ie/search/vob/house_books.jsp. If you search via Parish – so for Dunmanway enter ‘Fanlobbus’. Happy hunting!

LikeLike

Dear Sir/Ms

I would be very interested in communicating with you to discuss your research. I grew up on the market square in Dunmanway I am the author of Sam Maguire the man and the cup (mercier press, 2017) and Ballabuidhe 1615-2015, a social history.

LikeLike